Immunity-Pause: An Alternative Explanation for the Pediatric Flu and RSV Surge

Disclaimer: I am not an epidemiologist or a medical doctor. I am simply a psychiatry research student with a slightly-above-undergradute-level understanding of statistics, and a background in the philosophy of science – both of which I am relying entirely upon to write this blog post.

The immunity-debt, immunity-pause, and COVID-damaged theories

Currently, influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are surging, leading to very high numbers of children in the ICU. SickKids hospital in Toronto is even canceling surgeries to make room for more ICU capacity, as they are 27% over capacity and a majority of kids in the ICU are on ventilators. This is obviously really, really bad.

On Twitter and in the news (the usual suspects), “immunity debt” is being hotly debated as an explanation for the current surge. But the issue is that there are at least two definitions of “immunity debt” that are being mistakenly used interchangeably.

The most common definition of immunity debt I’ve seen says that 2+ years of mandates against COVID-19 have weakened childrens’ immune systems by preventing exposure to other diseases, like flu and RSV. This formulation of the immunity debt theory implies two things: first, that the immune system is like a muscle, which if you don’t use it, you will lose it; second, it follows simply that anti-COVID mandates damage our immune system, and so mandates are inherently bad.

The other definition of immunity debt, however, is different: proponents of this formulation agree that mandates drastically lowered exposure, and define “immunity debt” as the loss of some degree of population immunity due to this lack of exposure.

At first glance, these two formulations seem equivalent – if the first formulation is true, then the second formulation must be true; but if the second formulation is true, the first formulation isn’t necessarily true. The second formulation is consistent with an explanation that does not assume the immune system is like a muscle: first-time infections for flu and RSV are the highest risk infections. If you prevent the highest risk age groups (children) from getting exposed for the first time with mandates, then you offset the risk into the future, so when mandates are dropped there are more high risk kids in the first flu/RSV season, simply because they have not yet rolled the dice on first-time-infection. Here’s an easier way to think of it: when we lifted restrictions for COVID, there were a lot of high risk people who hadn’t been exposed to it yet who became infected for the first time (especially in December 2021 and January 2022). So, hospitalizations skyrocketed, even though the proportion of COVID cases turning into severe disease didn’t necessarily skyrocket. If you go from rolling the dice infrequently to rolling them frequently, you’ll roll snake eyes more often, but not with a higher probability of rolling snake eyes on any particular roll.

I prefer to refer to the second formulation of the immunity debt theory as “immunity-pause”1.

There is a third theory of the current flu/RSV surge: what I’ll refer to as the “COVID-damaged” theory. The COVID-damaged theory says that COVID is like measles: infection damages your immune system, making it harder to fight other viruses. Kids have been exposed en masse to COVID in the previous months, so their immune systems can’t handle flu or RSV. It’s basically the opposite of the immunity-debt theory (assuming by “immunity debt” you mean the first definition I listed).

Assessing the theories

One thing I’ve learned by following COVID-epidemiology closely since March 2020 is this: when assessing epidemiological theories, you have to ask (1) what does each theory predict the world should look like? and (2) what does the world actually look like? In this case, the best theory will have to explain the rise in flu and RSV cases, AND the rise in serious flu and RSV cases, in the pediatric population. It will also have to be consistent with the relatively low risk of severe outcomes from COVID-infection in children.

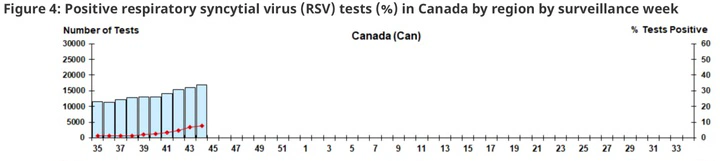

In an article in Global News today, Dr. Samira Jeimy argued that the immunity-pause theory (which the author of the article and Dr. Jeimy refer to as the second formulation of “immunity debt”) doesn’t explain the rise in pediatric respiratory hospitalizations – only the rise in total cases. But Dr. Jeimy fails to mention that there isn’t just a rise in total RSV infections, but a rise in total first-time RSV infections (along with a rise in total second-, third-, fourth-, etc.- time infections). That’s an incredibly important distinction because first-time infections are the highest risk for hospitalization. Given that the rise in hospitalizations is keeping pace with the rise in total infections (see RSV lab reports for week 44 in 2018-19 and 2022-23; tripling of respiratory hospitalizations in Ontario), immunity-pause seems to fit with the data. Furthermore, the immunity-pause theory is a simpler explanation (simpler in the sense that it posits fewer causal elements) than the immunity-debt or COVID-damaged theories: the latter two must accept that (1) there are more first-time infections due to lack of exposure; (2) there are more hospitalizations due to weakening/damage to the immune system.

On a related note, the COVID-damaged theory would predict that repeat COVID infections are higher risk than first-time COVID infections. Of course, someone who has been infected with a virus a second time is more likely to have been hospitalized or to have died than someone who has only been infected once, but that’s because they have rolled the dice a second time: if the probability of dying from first-time infection is 1% (of course it differs by age), then we’d expect 10 people out of 1000 first-time infections to die. If the probability of dying from second-time infection is .1%, then we’d expect 1 person out of 1000 second-time infections to die. So more total people die from COVID with successive infections, but that doesn’t mean that you’re inherently more likely to die from a second infection than a first. Given the decrease in the rate of death per COVID infection, it is unlikely that second-time COVID infections are higher risk than first-time infections (see important digression in footnote below).2

Of course, to say anything definitive about these three theories we need good estimates of what percent of new infections are first-time, second-time, third-time, etc. We don’t have that yet, so we must infer to the best explanation based on the prevalence of RSV, the percent of total cases leading to hospitalization, and the theoretical virtue of explanatory simplicity.

A warning against political bias in theory choice

One issue with debate around the current situation is political polarization. COVID mandates have been polarized massively. One way to categorize the most radical poles on COVID could be into the “mask-never” and “mask-forever” crowds. Conveniently for the mask-never crowd, the immunity-debt theory coheres tightly with their COVID politics. For the mask-forever crowd, the COVID-damaged theory coheres with their COVID politics. So be careful in this debate to lookout for political polarization.

Of course, the mere potential for political bias does not demonstrate that a given theory is true or false. Rather, you should simply keep this potential in mind when choosing your sources for information here. Someone ascribing to the immunity-pause theory (like myself) could just as easily be biased too: by accepting the immunity-pause theory, I could easily go on to try and justify mask mandates in every place I never step foot (e.g., elementary schools) while arguing they’re unjustified in a university setting. I could then try to gain your trust by highlighting the political polarization of people who accept the immunity-debt and COVID-damaged theories, by trying unironically to paint myself as an Enlightened Centrist. Polarization doesn’t imply that the centre is more reasonable than the extremes. Rather, the presence of polarization should make you skeptical of the motivations of everyone – left, right and centre – taking part in the discussion. Hopefully awareness of these political and personal biases in others will allow you and I the insight necessary to be rightly skeptical of ourselves.

Biases in mind, a strategic advantage of the immunity-pause theory is that it can help us avoid some of the neuroticism of the mask-never and the mask-forever crowds, at least in the short term. Sure, mandates for 2+ years came with the tradeoff of increased vulnerability to other diseases. But unlike the immunity-debt theory (which implies that we should not resort to mandates) and the COVID-damaged theory (which implies we should resort to mandates indefinitely), the immunity-pause theory allows for acknowledgement of the tradeoffs we made, while making room for strategic use of mandates to minimize the burdens on our health care systems while we slow down (but not totally prevent) the return of lost immunity. The immunity-pause theory can help us navigate polarization and the current health care crisis, at least if and until evidence emerges in favour of either the immunity-debt or the COVID-damaged theories.

We’re in a risky time. We should respond appropriately. I don’t know what that appropriate response looks like yet, but I’m more confident that we can approximate an optimal response if we act on the best evidence we have. I think current evidence and theoretical considerations favour the immunity-pause theory.

Nicholas Murray

“pause” borrowed from an article out of McGill University yesterday on this issue

Perhaps COVID leads to immune-weakening for other viruses, but not for itself. Measles seems to be like this. But the difference is that if you catch measles once, it’s very unlikely you’ll catch it again. The same is not true of COVID, and so if the COVID-damaged theory were true, we’d expect second-time infections to be higher risk than first-time infections